**edited to include photos of many I saw and sadly many I missed.

In the quest to test my comfort range and do things I normally would not be caught dead doing, I went last night to the Season Opener of the Metropolitan Opera, including attending the Gala Dinner following the opera which was Medea. This is a challenging piece rarely done, largely due to the stress on the Soprano who is to play this titular character and the one that made Maria Callas a STAR. Well a STAR was born last night and the story in the New York Times I feel captures the essence of this amazing woman who took on this role at her own request and with that a demand was met for more and today’s review only confirms this.

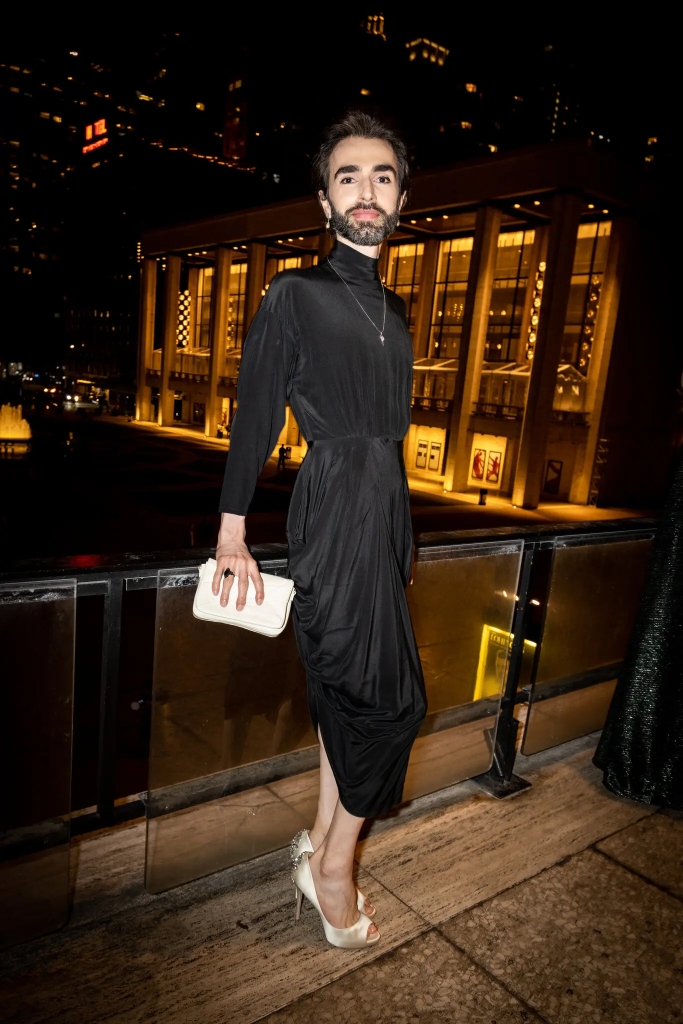

So off I went to what is a Black Tie event and often filled with varying celebrity beings and other essential Manhattan characters of wealth and import. I have no idea if any of them were there, as I don’t care one wit about those but the cast of characters that did arrive came in costumes that were worthy of another stage. There were many many men in gowns and the man in front of me sported a corset style coat with a peplum and a hair do that defied explanation. His eyebrows were covered with sequins and it was amazing to watch him walk up and down the aisle with many patrons trying to take discreet photos that he was more than willing to comply and then do the same of those who did not bother to ask permission. It was a pre show to the Opera that was to set the tone and sense of drama for the evening.

There were Men in Gowns with heels to match and with that I say it makes more sense than a Woman in one as it is way easier to pee. I tried to figure out how to navigate that idea of a train and gown in the Ladies room, on the Subway and commuting home and decided that between the undergarments, the shoes and glam required to carry it off, I could not do it; Instead I went with a Black Velvet Tux and Adidas Gucci tennis shoes. A the last minute a pit stop at the Gucci store I picked up a black silk tie to add to the ensemble. I was happy but my outfit was nothing in comparison to the woman nude beneath the crochet gown with just a nipple covering and g-string. Or the Versace clad group down to Kabuki style face masks, that was an ensemble best seen as it was impossible to describe as their feathers of their jackets were flying everywhere as were the pics as they posed for the crowd. Or the couple in full on dominatrix gear with the man’s breasts larger than his female companion. Her nipples were covered by the black leather bra her companion clearly needed. I kept thinking how comfortable could that be to sit for nearly three hours or next too. The man with the amazing hair I prayed did not lean to the right as it was view blocking.

To say an all day affair would be true as it took me two hours just for my make up so when I got there at 5 pm for cocktail hour, I was seriously in need for a drink. The opera began just after 6 and concluded just after 9 where many of us then adjourned to the park next door for dinner, which lasted well into midnight. Sadly none of the more colorful attendees made it to that portion but I was quite happy with my table of 10 and the flow of wine that followed.

My table was a delight, two women, one couple a single woman like myself, a couple from DC and two men, one from Manhattan who was there alone and left with the other woman, no comment as he said he would be leaving early into the dinner so coincidence? A charming man who despite shelling out $2500 for the evening oblivious to the fact that the Met had run a full season last year without missing a beat. Clearly that is support in absentia (or he really is not an opera goer unless he is compelled to, meaning free tickets). Attendance last year was erratic but many Operas had sold out and the season was well received and well publicized so that excuse I knew was bullshit but hey again he was in a Tux and there so he was not unlike all of us who seemed the atypical audience for an event like this.

But it was the Gentleman to my left who I spoke to throughout dinner, he was also from DC and had come up for the day to have a lunch with a former College friend and then came to the Met Gala. He has never lived in Manhattan and seemingly never gone to the Met before so his reasoning for attending I suspect was not for love of opera, but I will get to that later. He had relocated to DC after working for Amherst College, his Alma Mater, as a fundraiser for the last several years. All of his back story was classic aggrieved white male, down to drunken abusive father from a family of import from some small town in Pennsylvania. But apparently that “name” opened the door to a private exclusive all male prep school in Boston and with that onto Amherst. At the time Amherst was also exclusively male and he was clear about how he hated men. He said that his school years were hateful times in his life, but in his Junior year he went on an exchange year to Paris where he met a fantastic (female) Teacher whom changed his life. In other words he got laid. But anyway, he returned to Amherst, graduated, married and then the details seemed lacking or I was already killing a bottle of wine and missed some of them. Seriously this was getting boring and odd. After a while I thought what the fuck is this, an audition? And for what? He divorced wive #1 after 20 years and remarried a woman for the next 17, had no children with her but it was an unhappy time (I guess like Prep School abusive and unkind and no sex? Yes folks I did ask had been hazed and sexually assaulted) He has now five Grandchildren and in fact joined his adult daughter on the flight to NYC. He is now dating a woman, whom he met ironically, or coincidentally at the Opera in DC. As well clearly the Met is not his scene. He continued to remind me how he hated his youth and the boys and men he met or knew growing up, although I guess not the former schoolmate he had lunch with earlier but he LOVED women. Dear God I get it dude I really do. You are like all the aggrieved white males who despite it all it was never enough, not right in some way and that you cannot get over the tragedies in that time in your life. He said he was in therapy and felt he had worked through his problems and was willing to continue to be whole. And he was now doing something new and was quite successful at it and was enjoying it. What “that” was unclear and his knowledge of DC was slight as I had just returned, he had never heard of the hotel I was at which I thought a red flag as again much of his backstory which was missing some details that too mean one of two things, liar or con artist. Now neither can be true, but he is only sightly older than me, but again the whole name dropping but not name dropping was odd. He hated school and yet there are many many famous alumnae of Amherst of acclaim and that could have been his peers. And if you hated the place and the associations why in the fuck would you go back there and work? I would run run far away. And I have so I should know.

As the evening wore on and I was signaling the Waiters for more wine stat! He commented on that I was a good listener and yes, yes I am while swilling free booze and trapped I can be a great sound board. I cannot say the same for him, he forgot his hearing aids! Uh what? Okay then. But there is a point that either you are being hit up for money as I was at the last fund raiser, as you are sort of a given “mark,” or was it for sex? Either P – pussy or pocketbook – is what truly defines my worth at my age and neither are open for business unless there is free booze and glamour and then the AmEx is out of pocket, the pussy still no. It was exhausting and amusing all at the same time and of course this explains why I do not make a habit of this kind of thing. There are better ways to get a tax write off, really there are. I doubt he could tell you one thing about me other than I was a former Teacher and with that I am sure he was sure he had no wealthy widow to flop shack with. And despite loving women, I was not a potential fill in the blank. . And finally after the clock hit 12 my Gucci sneakers turned to dust I left to catch the Subway with believe it or not other Gala attendees. Yes folks we do travel on public transit here all the time at any time. And with that I got home made tea and organized all my stuff, doing laundry and hitting the sack exhausted but satiated with the story and the music in my head.

Today sharing the story with my Concierge I was laughing at the regalia and my own worries about what to wear but that I would not be doing that again regardless. I am sure there are other non profits that may have equally interesting fund raisers in the future that await my attendance, or not. And within that convo I was talking about the financial climate, the odd global strength of the US dollar despite inflation and how a British woman whom I also met at the Gala had commented on the rise of the homeless both here and in London and that it was distressing as she felt uncomfortable. Funny it is always women and when you come into a city of money that this issue stands out more than many. This is nothing compared I think to the West Coast or again I have become immune to it. She works for the company that live films and streams the Operas for theater and comes to this annually and noticed that this year it seems worse. I commented that I would love to go to London given that the Pound is dropping but with that the costs they easily offset the exchange rate, and regardless it is a lose-lose when you hear about families not being able to afford energy and food. It reminded me of my honeymoon in West Indies, also not good. And with that the woman who also works in the building or has a friend here was listening to my monologue, decided to comment that I was wrong about well all of it. She informed me that she follows the foreign market and that the Pound and the Euro are worth more and that costs in London are less than here and went on and on with shit that was so incorrect I knew it was time for a topic shift. I offered her my copy of the Times and WSJ to enable her to read my source and in which to further understand what I believe was happening in the global markets, knowing full well that she was not reading them, as this is not an educated woman. And I know this how? As when she heard me talking about Medea she thought it was a Tyler Perry show made into the Opera. Yes folks we gots some problems here. I am a what? A good listener and former Teacher and I seem to play those roles as well as any seasoned player can. But I am exhausted of it and I would just love to actually have a convo with someone who fucking reads! And with that many of the people I meet here have never set foot in Manhattan, never heard of the Opera, know nothing of that type of art form and frankly it is tragic, grim and pathetic. In fact when explaining that opera is often remade into pop culture I pointed out that Rent was based on La Boheme. The next question, “Did it have a Gay theme too?” Okay. But again some of my table mates who spent some serious cash were not exactly Rhodes Scholar’s either. As the song goes, Money can’t buy you class but it can’t buy you brains despite having an Ivy League credential I guess.

Oh well I am off to write an Opera of my own. It is called January 6th and told via the spirit of Ashli Babbit where it is King Lear meats Macbeth and all hell breaks lose and ends in flames much like Medea.